It was a standout session. Tom Hall zoom’ing into the main hall to give us a whirlwind tour across the global state of impact investing, with a decidedly optimistic tilt on the huge opportunities to pair impact with returns.

Tom is Global Head of Social Impact & Philanthropy at UBS, and he didn’t miss a beat. He swayed between discussion of the modern intersections between philanthropy and impact investing, as well as personal anecdotes of his globe-trotting to service high net-worth clients.

It’s the session that we received the most feedback about, and we’re excited to be sharing some of his slides, and some of his key insights.

Building an Impact Economy

With a room full of impact practitioners, the risk is that you’re speaking to the converted, but Tom managed to combine some valuable new insights, with tangible experience (and misadventures) from his global experience.

“I believe that we are all in the room today, because we want to build an impact economy. We want to see a world in which all people, and the planet, are valued as part of investment decisions.”

“There’s a billion people who don’t have access to basic health care, yet we know the value to society of $1 spent on health creates $10 of additional productivity. Not to mention the human cost of just not being sick. I was in Vietnam last week, and I saw the difficulties smallholder farmers were having, who want to feed their families; chopping down a hectare of mangroves, means releasing 840 tonnes of carbon, which is a lifetime supply of carbon for someone in the developing world, for just $500. That hectare of mangroves is worth so much more than that.”

“We have to create a system where we can transfer the value of that so that farmer doesn’t need to chop down those mangroves.” Tom says.

$10 Trillion of Philanthropic Giving

Tom is no stranger to big numbers, and while he recognised the global impact market had pushed above $1 trillion, he quickly cajoled us to think bigger. That the size of the problems in the world today will need investment of many multiples of that amount.

And to get there, we’re going to need to work together.

“In the last 10 years, the global value of billionaires has gone from $1 trillion to $7 trillion. And many of that first generation wealth creation is not going to all be left to families, it’s simply not. Forbes had an article where they estimated the total philanthropy maybe as much as $10 trillion by the mid 2030s.” Tom says.

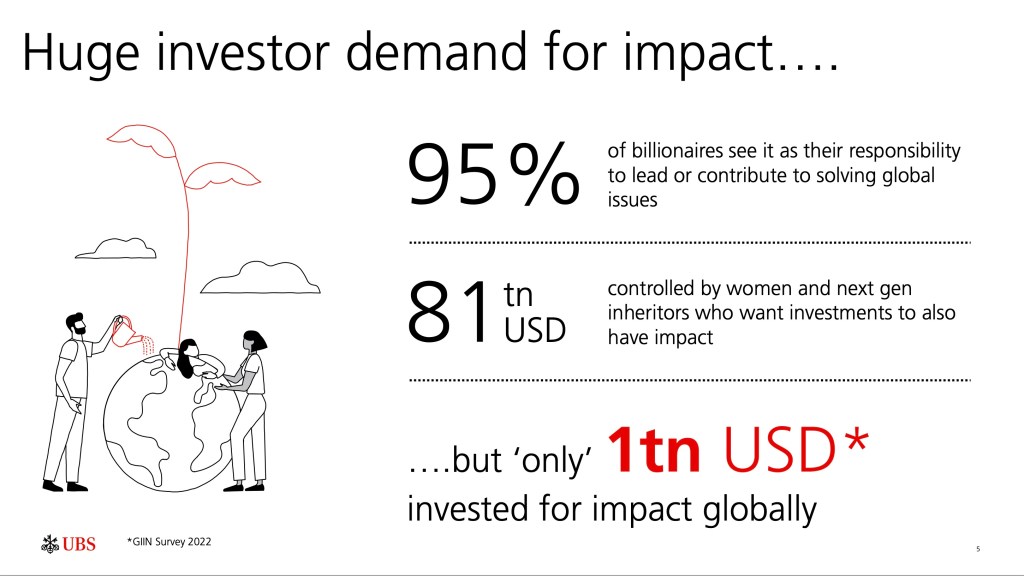

“Last year 95% of our billionaire clients told us that they see it as their responsibility to try and solve the pressing social and environmental problems the world’s facing, through their philanthropy yes, through their investing, but also through their operating businesses. It’s hugely encouraging.”

“Yet, in spite of all this demand, GIIN estimated at the end of last year that there’s only around a trillion dollars in impact investing, Now I don’t mean to denigrate this, I think it’s a fantastic progress. But it’s not the $30 trillion needed. So what are we going to do? How are we going to push further and break the barriers and create a pathway to really finance the SDGs at scale and to build an impact economy? Well, I think we just simply will not get there, unless we radically reimagine how we all need to start working together for impact.”

“And listening into the conference, there’s already so many of you doing this already, where philanthropists, investors, local communities, governments, and social enterprises are starting to work together, along with academic institutions. It’s only going to be through partnerships, that we’re going to have a hope.” Tom says.

We Need to Simplify Impact Measurement

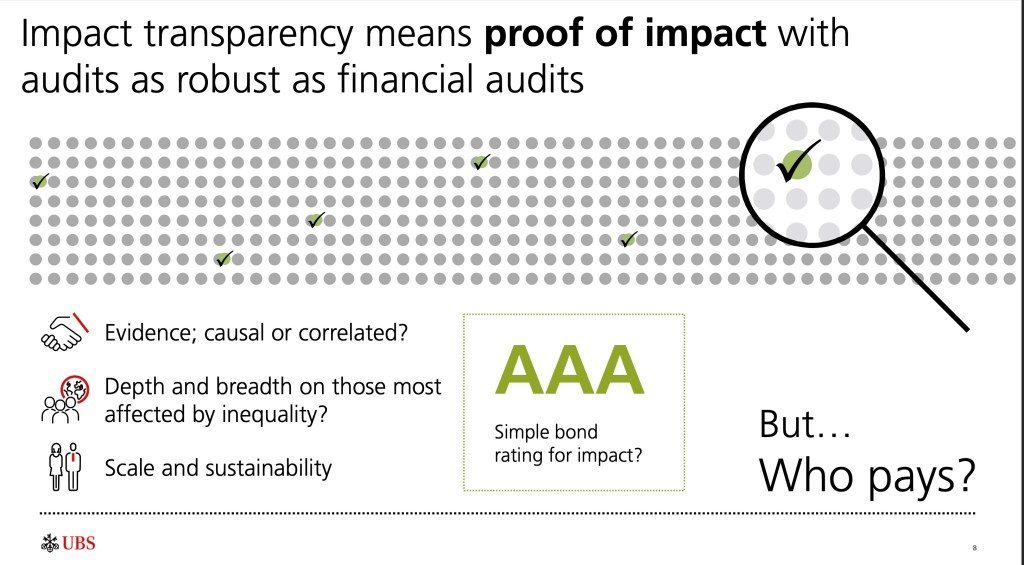

All impact investors have struggled with negotiating the alphabet soup of impact frameworks, and while there has been a welcome process of consolidation of late, it’s still complex.

I’m sure Tom has had more conversations with more people about impact measurement than anyone else in the room, and he was crystal clear when he said the systems must be made more simple. People simply won’t engage if we don’t.

“There’s been a proliferation of different impact measurement methodologies out there. And it’s confusing people. I’ve worked with many billionaires who give hundreds of millions away to very causal impact, which has been measured through randomised control trials, they really understand what impact means, but, they do not invest in impact investments, because they simply don’t believe it, they don’t believe the data. So unless we can start to reassure people, as to the impact that’s being achieved, when we invest for impact, then we’re not going to see the flows, from even some of the early adopters.”

“I think we should try and keep it fairly simple, we need really simple to understand methodologies around impact measurement. Just get to the heart of what people need to know so we can start comparing apples with bananas, and ultimately, the most important thing is evidence. Why do we settle for evidence that’s not causal?”

Impact Risk-Adjusted Return – New Models For Scale and Impact

We need to rethink some of the core systems of philanthropy, so we can reallocate scarce capital to have the biggest impact possible. And once the projects are identified, Tom suggests we also rethink how we rank them for risk, we should focus on a model of ‘impact risk-adjusted return’, so investors can decide what they want to pay for impact.

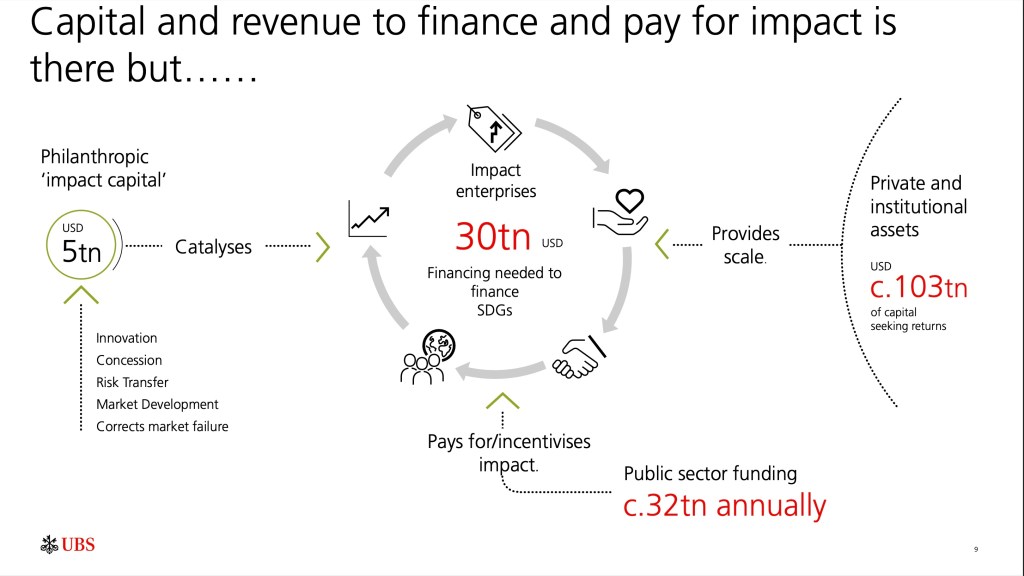

“What I find frustrating about the impact world and landscape, having worked in this for the best part of 20 years, is the capital is there, the revenue is there to pay for impact, but the different actors in the system and in the economy are not doing the right things.”

“So let’s take the $30 trillion we need for the sustainable development goals. So we’ve already touched on the philanthropist, you’ve got $5, maybe it’s $10 trillion, it’s insufficient, and they keep setting up models on their own, that can never ever solve the problem.”

“I’ll just give you one example. And this is again, not to denigrate anything. Scholarships are a fantastic way to get one child into tertiary education, often from really disadvantaged backgrounds. But if you wanted to scale that scholarship model, particularly the endowment based scholarship model we’re using all over the world for every child who might need one, we’d need $60 trillion in an endowment. There’s simply not enough money to use that model, we have to think differently.”

“We’re saying to people, well, we can’t really offer you this product, because it doesn’t meet the market risk adjusted return so we can’t even possibly let you take that risk. I was with a client last week in Vietnam, and they were saying to me, please stop telling me that you can only sell me market-rate risk-adjusted return impact investments, just start telling me what impact I can achieve, at what price and I will decide whether the return is good enough. I can work out what the trade off is between the impact of an educated child, for example, and whether I get a 9% return 15% or 20%.”

“So I think this idea of impact risk adjusted return is something that we really need to push for. and reimagine how we frame and position these things for investors so that they can make the decision.”

“And, we want to expedite that we’re delighted to announce a new partnership with the London School of Economics called the 100x Accelerator. Where a philanthropist is putting in $50 million, UBS is putting in $5 million, to literally try and systematically screen candidates from 1900 to get 20, to find future impact unicorns, businesses, or social enterprises that can impact a billion lives. And we want to expedite them.”

Slashing the Cost of Education, For Everyone

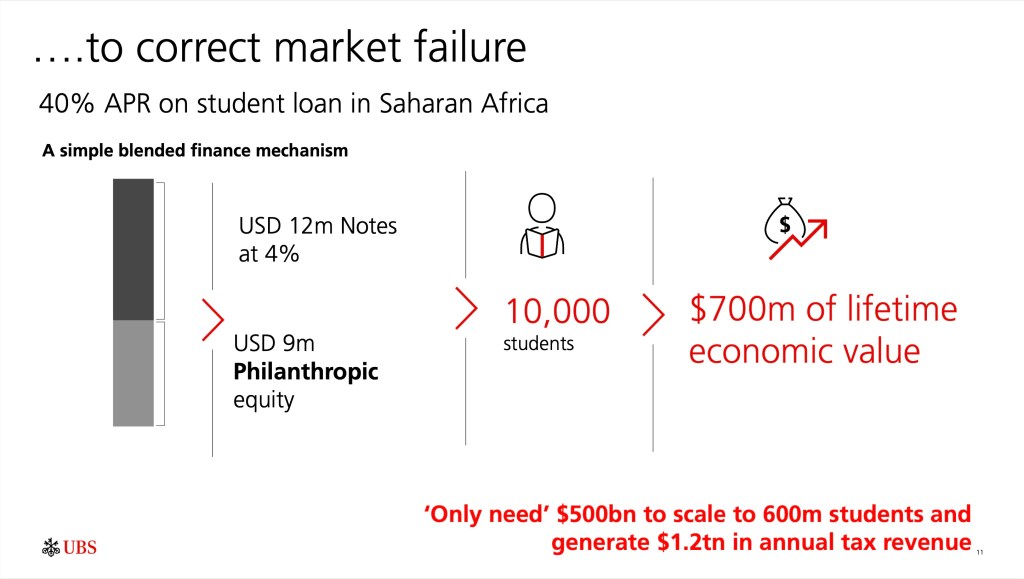

With excellent timing, Tom brought some movement back to the room, asking us who had got a loan for their education, and who had paid less than 10% interest on that loan. Most of us were within the threshold, and we were then shocked to hear that those in countries like Rwanda are confronted with repayment rates that are prohibitive.

“Why in God’s green earth is a young woman in Rwanda, who’s struggled her whole life to get through education in the first place, being charged 40% on a tertiary education to get the education she deserves.”

“It’s market failure, it’s a perception of risk and it needs to be solved and it can be.”

“One of the ways that we addressed this was a very simple blended finance mechanism where philanthropic investors, into a fund, took a first loss position, they were prepared to carry some of the risks to address this perceived risk, this young woman is not going to pay back her loan. And that meant we could borrow follow-on money from institutions not at 40%, but at 4%. And that $21 million invested in 10,000 students over a 10 year period will get repaid at around 9%. That’s what the track record already shows. These women are great credit risks, not bad ones. And they will then add to their economy $700 million of lifetime economic value. I mean, we should be investing in this in scale.”

“And this could be hugely scalable, it would only need $500 billion, not $60 trillion, to give this kind of financing for education for every student in the world, 600 million who might need one, and add $1.2 trillion to our economies.” Tom says.

Pay for Outcomes

We can’t ignore the uncertainty and hesitation that many investors still feel for the idea of investing in impact. It’s counter to the foundational model of finance for so many, and so we need to ease them into it.

Governments have a big role to platy here. They can lead the way by simply paying for outcomes, and seeding funds with first loss capital.

“And we’ve had a lot of experience in these outcomes contracts at UBS over the last decade. And each and every time we do them, we’re blown away by the efficacy and the impact. So a simple example in India, the US government are paying for a hospital, it was clean and well run, in a three year period about 400 hospitals were accredited, so this should save 6000 lives, and that $3 million worth of risk capital will get repaid at 9% IRR. Again, 200,000 children in India learned two and a half times faster, at 50% of the cost of the control with the same intervention. So what that says is outcomes purchasing actually changes the entire system in terms of efficiency measurement to data, it’s hugely efficacious.”

“Each time we see this, we’re able to convince governments that they should start participating in buying outcomes. And off the back of those two impact bonds, we lead to a $300 million worth of outcomes potential from several global governments, Ronnie was very involved in the education outcomes fund, that’s allowed, UBS to just do the same thing. Again, you know, this, this asset class is not well understood, people are worried about it, so we got $20 million of philanthropic capital in a blended fund, again, taking first loss, and that’s allowed us to raise another $80 million from institutional investors to, for the first time, start investing in some of the poorest communities in the world, their education systems, in countries like Ghana.”

“So this intervention will see about 15 outcomes contracts in lower middle income countries, and should impact about 5 million children. It’s still in the foothills of where we need to be, but it’s encouraging to see and I always love listening to Sir Ronnie, because he always says the J curve that we saw in venture capital in the 80s, is the same J curve we’re seeing now in impact. And I believe him and it’s definitely coming.” Tom says.

Nature Needs a New Business Model

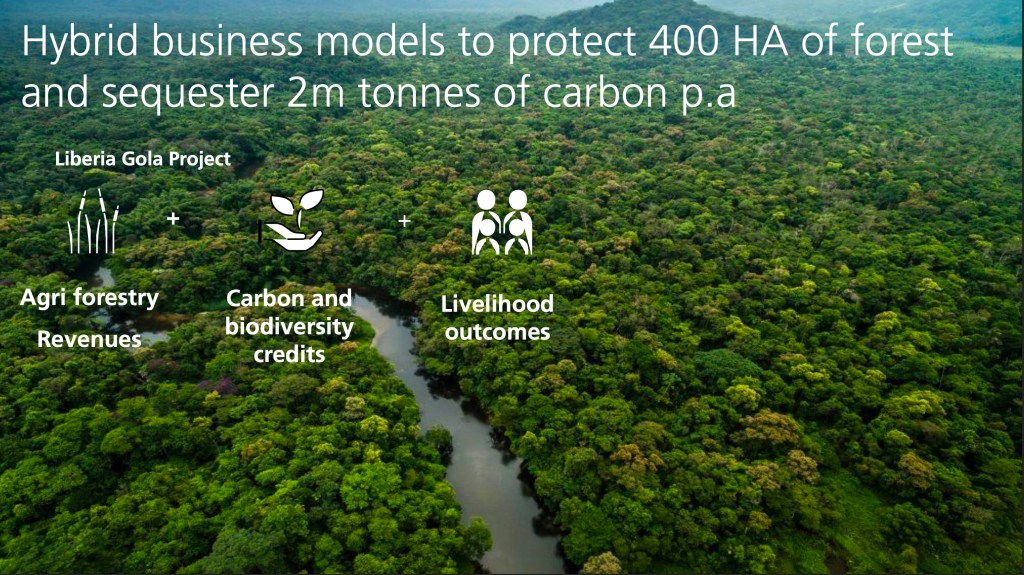

Another market failure is in the way our economy values natural capital assets. It’s a painful mismatch when the market drives those in poor countries to chop down trees, rather than conserve the forest to provide a sustainable income. But we have levers for change, there are ways to drive capital to create powerful long-term outcomes.

“In some instances we need to create entirely new business models. We have revenue base models that just don’t pay enough profit. So in the nature based solution space, we see this whether it’s shrimp farming in Vietnam, as I saw last week. Or agribusiness, cocoa farming within the Liberian rainforest, just doesn’t pay enough revenue. So it’s not really investable. You can add additional revenue from carbon credits if you can get the carbon market working or biodiversity credits, even then sometimes that doesn’t work. We’ve just launched a new pilot in Liberia where we’re getting livelihood outcomes paid for by the US government, because they recognise that if you have a sustainable business and those families are sending their kids to school and they’re healthy and well educated, that has a long term GDP impact that should be paid for today.”

“So by pulling that all together, we feel we can create a model that can actually impact 400 hectares of forest and sequester 2 million tonnes of carbon.”

“Ultimately, I believe that if we all play our part, if we all bring our combined resources, not only can we build an impact economy, but we can meet the SDGs, and I believe that we will. I’d be delighted to partner with you on that journey.” Tom says.

All slides are courtesy of UBS and Tom Hall.